By Anne de Courcy

Wall Street Journal

Nov. 29, 2018 6:34 pm ET

For several decades in the late 19th century, Caroline Schermerhorn Astor was the undisputed queen of American society. A tall, well-built woman of imposing and dignified appearance, she wore her black hair majestically on top of her head and dressed in suitably regal clothes—black and purple velvet were among her favorites. Caparisoned with an intimidating array of diamonds, she resembled an idol bedecked for ceremony.

Like all successful cult leaders, Mrs. Astor took herself and her diktats with impressive seriousness, cultivating her mystique with an impervious manner. “No one ever knew what thoughts passed behind the calm repose of her face,” said Elizabeth Lehr, a fellow socialite. But everyone followed the rules Mrs. Astor laid down, from the number of courses to be served at dinner (seven followed by coffee) to the appropriate time to arrive at the opera (never less than an hour late).

The world Mrs. Astor presided over would seem, to our eyes, stultifyingly futile, powered by the great wealth that gave the Gilded Age its name and governed by a rigid etiquette. At the age of 9, the young scion Cornelius Vanderbilt IV would set out daily with his mother on a two-hour round of visits to their Newport neighbors. “I could never comprehend why we should spend every glorious summer afternoon,” he later wrote, “showering the colony with our calling cards when we had already nodded and spoken to our friends several times since breakfast.”

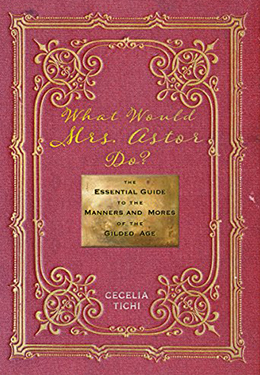

The exteriors of life in this upper echelon are the subject of Cecelia Tichi’s “What Would Mrs. Astor Do? The Essential Guide to the Manners and Mores of the Gilded Age.” We learn what the people of Mrs. Astor’s circle ate for dinner, what they wore and when, how to mix their cocktails, how a gentleman should hand a lady into a carriage. Occasionally the exhaustive list of details reads like a catalog, as we are told what the interiors of elevators looked like, and how the washrooms in private train cars or the drawing room of a Vanderbilt yacht were furnished.

At the beginning of Mrs. Astor’s reign in the early 1870s, high society consisted of those families that could claim to be descended from the original Dutch or British settlers and whose fortunes had been established sufficiently early for any hint of ill-gotten gain to be washed away. They lived quietly, dining with each other in their brownstones and refusing to wear their new dresses (in sober colors, naturally) for two or three years lest they appeared too fashionable. Here Ms. Tichi, a professor of English and American Studies at Vanderbilt University, is very good on the feel of New York’s streets: “Odors of acrid coal smoke, drizzling soot, and the screech of the El trains as they stopped and started along Sixth Avenue assaulted the ears, eyes and nostrils. Roadways rang with voices, clanging bells, and hooves scraping and clattering on the pavement.”

After the Civil War, vast fortunes were made from railways, mining, wheat and real estate, a tsunami of new wealth that threatened to overwhelm the Knickerbocker establishment headed by Mrs. Astor. The two were cleverly melded together by Ward McAllister —the self-appointed arbiter of American society and the customs it should follow—thus launching the Gilded Age: $100,000 dinners, cotillion favors from Paris, jewels without number and “cottages” of 30 rooms in the elite’s favored summer resort of Newport, R.I.